Hello,

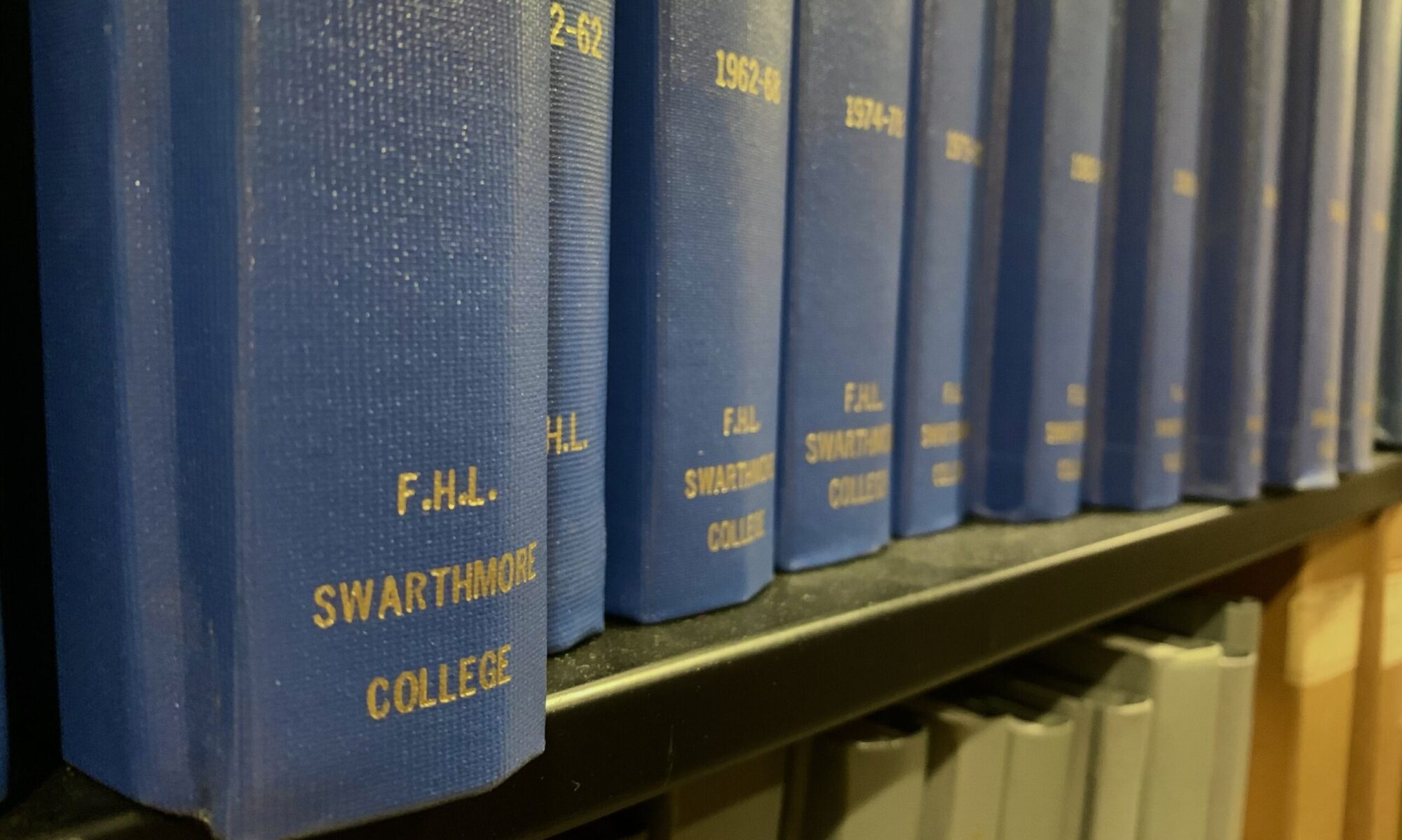

My name is Zahara Martinez and I am a senior at Swarthmore College from Irvington, New Jersey. This summer I have partnered with the Friend’s Historical Library of Swarthmore College and fellow student Whitney Grinnage-Cassidy ’24 to document the names of people enslaved by Quakers during the 18th and early 19th centuries.

The topic of African-American genealogy always interested me, but the project became incredibly personal following the sudden death of my grandmother in the very beginning of the summer.

Regretably, for most of my life my grandmother was a shadow. She lived in Jamaica, and never moved to the United States as some of her children, including my mom, did. She was a presence that I did not see, but I knew she was there. From the times she visited my family in the United States and when I visited Jamaica as a child, I am able to piece together a fragmented picture of her personhood. I remember her deep belly laughs, the way she always stated her opinions without sugar coating them, and the way she always smelled like the best perfumes.

I found myself at her funeral early July wishing I knew more about her and that I got to spend more time with her. However, I got to see the hundreds of lives she touched. She taught for over 30 years, and a huge crowd that represented only a small fraction of the many people she taught or taught with came to give their tributes.

Family makes a person whole, so knowledge of one’s ancestry is power. Unfortunately, many black people in the Americans have been barred from the privilege of knowing who they come from because of the brutal practice of chattel slavery, the neglect that there has been of documenting of black communities if they weren’t outright destroyed.

The enslaved people that Whitney and I have documented were exactly that– people. They were people first and foremost. They had their own personalities, likes, dislikes, favorite foods, dreams, and talents. They loved other people and were loved by other people. Like my grandmother, they touched lives.

They were punished for this very humanity by means of torture, extreme labor, familial separation, the criminalization of their education, physical abuse, sexual abuse, and other twisted means of dehumanization.

The names that I have been documenting are just symbols, placeholders representing the whole person that each and every one of these enslaved people were. They are also only a small fraction of the millions of black people who were held against their will and subjected to living a life of misery and servitude. The only reason we know their names is because Quakers were fastidious record keepers. These people deserved to be known, and their memories deserved to be claimed by their family members.

It’s a privilege that I have got to work on this project this summer, and I hope to continue this work in the future.

Zahara